When is it Reasonable to Draw Your Knife in Self-Defense?

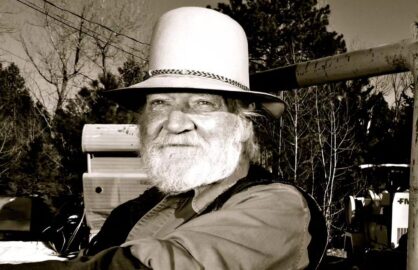

When is it reasonable to draw your knife in self-defense? This is a question many have pondered, but without some knowledge of the legal system and professional defensive knife training, the answer can be murky. Edged weapons expert Chad McBroom of Comprehensive Fighting Systems sheds some light on this topic and offers some valuable points of advice.

“Knives are considered deadly force weapons by the courts; therefore, they should only be used in situations where the individual reasonably believes he or she is in danger of great bodily harm or death, or to protect another from the same,” says McBroom. “Great bodily harm is a legal term that seems to be hard to define, but can generally be described as an injury that results in permanent disfigurement or loss of function.”

The 3 Factors You Need to Consider

McBroom goes on to explain that there are three factors you should consider in determining whether the use of deadly force is warranted: Ability, Opportunity, and Intent. Your threat must display the ability, the opportunity, and the intent to cause death or do you great bodily harm for your use of deadly force to be justified.

1. Ability

“Ability can represent a number of things, such as the person’s physical stature or skill level, the presence of a weapon, the presence of additional attackers, or anything that gives the attacker the ability to inflict serious bodily harm,” explains McBroom. Clearly, for a person to pose a deadly threat, they must possess something that gives them a distinct advantage over you, whether it’s a weapon, their size, their physical skill, or some other recognizable means.

2. Opportunity

McBroom describes opportunity as, “the immediate opportunity to exercise that ability, which is typically viewed through the lens of proximity.” In other words, “The threat must be close enough to use whatever weapon or physical advantage they have,” says McBroom. For example, a person armed with a knife would have to be much closer than a person armed with a gun to use their weapon against you.

3. Intent

“Intent is the verbally or physically expressed will to due physical harm,” says McBroom. Saying, “I’m going to kill you,” pointing a gun at you, or winding up a club as if to swing at you are examples of intent. Obviously, someone already engaging in the physical act of trying to do you harm is displaying intent.

All three factors must be present if the use of deadly force is to be justified and defensible. Someone standing behind you at the checkout line who is carrying a handgun in an open-carry state has the ability and opportunity, but is not displaying intent. Someone holding a knife on the other side of a fence screaming, “I’m going to gut you,” is displaying ability and intent, but is lacking opportunity because of the barrier created by the fence.

Repercussions

If you do end up using a knife in self-defense, you’re going to have to face the legal system, so it’s critical that your actions are justifiable. You could wind up standing before a judge and jury of your peers. The gruesomeness of the scene could make you look like an axe murderer to a jury, which is why McBroom stresses that you should only use your knife to the extent needed to stop the person attacking you. “If it comes down to it, use your blade violently and without hesitation until the threat is no longer present; but once the violence against you stops, you must stop,” McBroom advises.

According to McBroom, there are conditions when it may be appropriate to draw your knife as a means to ward off an attacker who is displaying ability and intent; whereas in other circumstances it is better to keep your blade concealed until the last moment. “Every situation is unique, and acquiring the knowledge and experience to make those decisions is part of the responsibility of carrying a knife for self-defense,” McBroom concludes. “That is why it so important to seek out proper training.”

0 comments